Safeguarding our cultural heritage: Addressing change and continuity of Bram and Carnaval in Belize

Safeguarding our cultural heritage: Addressing change and continuity of Bram and Carnaval in Belize

Safeguarding our cultural heritage: Addressing change and continuity of Bram and Carnaval in Belize

By Phylicia Pelayo

Abstract

From November 2013 to May 2014, the National Institute of Culture and History (NICH) through its Institute for Social and Cultural Research (ISCR) carried out a community-based pilot project to inventory several cultural celebrations. Cultural celebrations were defined as festivities fixed to a particular date or time of the year and rooted within a community’s history or cultural heritage (i.e. fiestas, festivals, ceremonies etc.). The inventorying process involved the identification, documentation, and research of various cultural forms associated with an array of celebrations. This paper examines two cultural celebrations which were inventoried during the project namely Carnaval as practiced in Caledonia, Corozal and the Christmas Bram held in Gales Point Manatee. The paper also maps the cultural changes occurring in each community and examines the potential for the continuity of these practices within the communities discussed. This project was viewed as an essential step in the national implementation of the 2003 UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage as it allowed communities to participate in the inventorying of traditions and eventually develop mechanism to safeguard specific practices.

INTRODUCTION

In his article addressing intangible cultural heritage, ethnomusicologist Wim Van Zanten states, “Culture can only have continuity if people enjoy the conditions to produce and re-create it.” (2004). Van Zanten statement sets the tone for this paper as it acknowledges that cultural practices are enacted based on an array of factors in the community – religion, politics, economics- changes in these conditions which cannot be controlled also modify how cultural practices are done. He also acknowledges that cultural practices are “re-created”, culture is not static. Cultural actors may perform a dance for decades but each time the dance is done it is not done in the same exact fashion, it is stylized, performed, and enacted differently based on the social conditions, the position of the performer, and of course the audience among other factors.

Presented in this paper is Bram, a Creole festivity held during the Christmas season and today has mainly survived in the community of Gales Point Manatee and Carnaval, a Mestizo pre-lenten festivity celebrated in the period immediately preceding Ash Wednesday. Both are communal traditions that were once popular in various communities but today are no longer widely practiced. This paper maps the cultural changes occurring in each community and examines the potential for the continuity of these practices within the communities discussed.

A COMMUNITY-BASED PILOT PROJECT

On the 4th December, 2007 Belize ratified the 2003 UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH). The Convention aims at safeguarding ICH (in accordance with international agreements on human rights) that has been identified and defined as such with the participation of communities, groups and relevant non-governmental organizations (UNESCO). Subsequent to Belize’s ratification, NICH has served as its implementing agency. As part of UNESCO’s global strategy on capacity-building, Belize was provided with assistance in 2012 and 2013 for the Convention’s national implementation and the development of a framework for safeguarding ICH. With funding provided by the Japanese Funds-in-Trust, UNESCO facilitated workshops in which community bearers of ICH, cultural stakeholders, as well as government and non-governmental representatives were equipped with the knowledge and importance of the ICH Convention.

In October 2013, the Banquitas Action Plan was drafted by participants of a national workshop focused on community-based inventory of Belize’s ICH. The community-based inventorying approach recognizes the importance of community bearers of ICH or cultural practitioners “as traditional custodians in the preservation of ICH and places them at the center of the inventorying process” (UNESCO, 2013). In its preamble the action plan emphasized the importance of safeguarding ICH as part of raising awareness about culture and promoting social cohesion. It also highlighted that communities take ownership for the safeguarding of their cultural forms to ensure their continued transmission.

The workshop and action plan provided the framework for a six month community-based inventorying pilot project to document an area of Belize’s ICH. This community-based project centered on the need to involve communities, groups and individuals in safeguarding their ICH (UNESCO; ACCU, 2006). After several discussions it was agreed the first phase of the action plan would focus on the inventory of Belizean Cultural Celebrations. The participants defined cultural celebrations as festivities that are fixed to a particular date or time of the year and are rooted within a community’s history or cultural heritage. Cultural celebrations such as fiestas and festivals normally encompass several domains of ICH (i.e. traditional craftsmanship, rituals and social practices, oral traditions and expressions, etc.) and therefore allow for the inventorying of multiple cultural forms. The inventory of cultural celebrations across ethnic groups also allowed for inclusivity between communities and groups of various backgrounds. Participants formed a network informally called the ICH Working Body. Members of the working body were directly involved in carrying out the inventorying during the project. NICH through ISCR functioned as the secretariat for the body during the project.

The inventorying process involved the identification, documentation, and research of the various cultural forms associated with each cultural celebration for the purpose of preservation, protection, and promotion. At the community level, the project aspired to enhance the various traditions by creating awareness about its importance within the community and to Belize’s cultural diversity.

This project served as the first tangible step towards the development of an inventory of Belize’s cultural forms. The development of a national inventory (or inventories) of ICH is required to fulfill the country’s obligation as a signee the convention.

The inventorying process of the project was carried out between November 2013 and April 2014. During that time, seven cultural celebrations – Los Finados, Yurumein, Las Posadas, Ox’lajun Ba’aktun Ceremony, Christmas Bram, Carnaval, and La Semana Santa were inventoried. The inventorying process involved the collection of oral and audio-visual information about celebration’s history, social function, associated cultural forms and urgency for safeguarding. This was carried out in multiple communities where possible. Apparent throughout the project was that these celebrations all shared similar safeguarding challenges. However, of the seven celebrations Los Finados, Christmas Bram and Carnaval appeared to have faced the greatest risks of discontinuity.

METHODOLOGIES

The ethnographic information presented in this paper is of a qualitative nature and was collected through several initiatives. Primary research about Carnaval was collected by the author from 2010 – 2013 during which ISCR carried out field visits to Caledonia. In the period leading up to and during the practice of Carnaval, information was collected through participant observations and several semi-structured interviews carried out by the author and her colleague Rolando Cocom. In 2014, the three days of Carnaval were inventoried during the pilot project. The festivity was recognized by the ICH Working Body as an important tradition in Northern Belize. Participant observations and semi-structured interviews were also carried out by the author and members of the ICH Body during those three days.

In December, 2013 several persons from the Working Body (not including the author) visited the Gales Point Manatee to collect ethnographic information on the Christmas Bram as practiced on the 25th and 26th December. Participant observations and several semi-structured interviews were carried out with community elders and participants of the celebration. In June, 2014 the author acquired additional information by conducting semi-structured interviews with other persons in the village.

“MALANTI” OR GALES POINT MANATEE

The most extensive ethnographic research written about Gales Point Manatee or “Malanti” (as referred to by local residents) is a published thesis by Ritamae Hyde (2012). Hyde’s research, “Stone Baas People: An Ethnohistorical Study of Gales Point Manatee” provides an in depth look into the history and heritage of the community through historical research and oral histories gathered during her field work in 2008. Myrna Manzanares, former president of the National Kriol Council and originally from the village also provides an auto-ethnographic account of the community’s cultural heritage by examining the change and continuity of various cultural forms (including the Christmas Bram). As Hyde and Manzanares have provided much of the groundwork, this paper will not elaborate on the history of the village and various cultural forms but provide a brief backdrop as needed to place the cultural celebration that is “Christmas Bram” into its social and cultural context.

Gales Point Manatee is a Creole or “Kriol” village located in the southern end of the Belize District on a peninsula in the Southern Lagoon area. The history of the village revealed through Hyde’s research, places Gales Point Manatee as a secondary maroon settlement established in the 18th and early 19th century (Hyde, 2012). Due to the severe conditions of slavery, several revolts occurred along with accounts of desertion. O. Nigel Bolland (2003) references the formation of maroon settlements by 1820 as reported by Superintendent Arthur who mentions slave towns long established in the Blue Mountains north of the Sibun River. Through oral testimonies collected through Hyde’s research it is believed that these maroons first settled in the mountains and areas surrounding Gales Point Manatee and later resettled in the current location of the village (2012).

Contributing to the successful growth of this maroon settlement was the remoteness and difficulty in accessing the village (Hyde, 2012). Today the village is still relatively remote and not easily accessible by public transportation. It has largely remained a rural settlement with a very small population of 296 persons and continues to experience out-ward migration. The village has retained an almost homogenous ethnic make-up with 89% of the population identifying as Creole according to the most recent population census (Statistical Institute of Belize, 2013). This large percentage of Creole ethnicity can be traced to the village’s early African ancestry, an ancestry which is still reflected in surviving cultural practices such as the Christmas Bram.

Figure 1: Map showing Gales Point Manatee. Retrieved from here

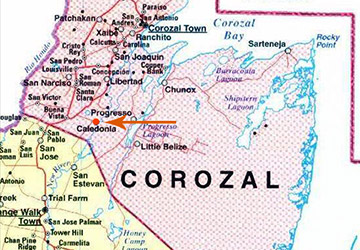

Figure 2: Map showing Caledonia. Retrieved from here

CALEDONIA

The village of Caledonia is tucked away from the neighboring towns of Corozal and Orange Walk, located off the Philip Goldson (Northern) Highway near Buena Vista Village. The village is accessible through the cut off from Buena Vista village or through the Corozal-Chunox road. Apart from research carried out by ISCR personnel, to date no extensive ethnographic research has been carried out in the village. The only published ethnographic research about the community is by Rolando Cocom (2012) in his paper on Carnaval in Caledonia. Cocom provides us with a preliminary ethnographic profile of the tradition and briefly describes the development of the community. Oral testimonies collected during field visits states that Caledonia was originally a small logging camp and mainly became settled during the growth of the sugar industry in Northern Belize (Pech, 2011). Frequently, elders noted that the area was originally owned by a “Scotsman” or Scottish person; however they are uncertain of his name. What is clear is that this Scotsman owned much of the land that forms present day Caledonia. Persons from various neighboring communities came to work in Caledonia for the owner. Today community elders, cite relocating from other communities for work in Caledonia, or having been a child when their family relocated. The cultural landscape of the community was much more diverse than today as Caledonia had a mixture of Maya, Caste War immigrants, Europeans, Jamaicans and possibly African/Creole labourers (Cocom, 2012). Today the village has 1400 inhabitants and an almost homogenous Hispanic/Mestizo presence with over 85% of the population listed as Mestizo (Statistical Institute of Belize, 2013). For most of the adults, Spanish is their first language. Elders note that there has been an influx of Central American immigrants to the community over the past few decades (Pech, 2011) (Olivarez, 2011).

The village has retained a rural atmosphere, and more than half of the population has remained engaged in some form of agriculture (Statistical Institute of Belize, 2013). There are signs of cultural changes within the community over the years as evident in the housing styles. Modern concrete houses have begun to replace the traditional cohune-based thatched structures and colonial designed wooden houses. In 2013, the author also observed that the first Asian store was opened in the community. Catholicism represents the largest religion practiced by 63% of the community and was brought by Caste War (1847-1901) migrants who sought refuge in Northern Belize. It is believed to have been introduced to the village during its early development by priests from nearby communities such as San Estevan (Olivarez, 2011). Today, other denominations practiced include Seventh Day Adventist, Pentecostal and Jehovah Witness. The only formal educational institution in the village is the Caledonia Roman Catholic Primary School. A large number of students further their secondary school studies at La Escuela Secundaria Tecnica Mexico in the village of San Ramon about ten minutes from the village of Buena Vista. There is one police station and one health care center available.

Although information was not specifically collected about other existing cultural festivities, through personal observations it was noted that the community still retains various cultural forms and intangible heritage knowledge such as craftsmanship, traditional herbal knowledge, cuisine etc.

BACK IN THE ‘OLE DAYS

In their article, Christmas and Bramming in Belize City, anthropologists Laurie A. Greene and Joseph Rubenstein (1991) defined ‘bram’ as “a community based celebration that includes music, dancing and feasting”. This description highlights the main activities of bram; however, it is also a general description applicable to an array of cultural celebrations today. Their article describes the ritual and festive features of Christmas in Belize City in 1989. By this time, the tradition had mostly disappeared from the city’s Christmas rituals and was practiced only as a private family affair within few families.

Residents cited factors such as the emigration of individuals and families to the United States as the one of the main reason for the disappearance of the tradition in the community (Greene & Rubenstein, 1991). Emigration is believed to have led to the separation of families and community members. Although in some cases, the separation was only temporarily, there was a noted change in the cultural identity of those who returned. As one interviewee responded to the dramatic decreased in the tradition’s practice “they go away and they come back and think this is all sort of primitive, I think that is why…Yeah I think so too…Our kind of native dance is a lot of bramming.” (Greene & Rubenstein, 1991). Recurrent throughout the interviews is the gap in the transmission of the tradition between the older and younger generation. “When [the] old come they want to bram, but the young–I don’t know. There is an Americanizing element, [the] old sort of want to recapture something, but the young have no inclination. They want to be American, not British” (Greene & Rubenstein, 1991).

Almost ten years prior to Greene and Rubenstein’s research, the Christmas Bram was already regarded as a fading tradition. In Gladys Stuart’s (1978) The Christmas that went before, she briefly highlights the cultural changes of the Christmas season that was occurring during that period reflected in the discontinuity of various hallmark activities of the season i.e. the arrival of the Waika woodcutters in Belize City to participate in the Bram, the preparation of the traditional holiday dishes, and the ritual house cleaning and decoration by families. While Stewart does not explain the factors creating these changes she provides us with a description of Bram during that time.

The town came alive with the throbbing of drums-the bram! Groups of friends would gather at a home with the furniture pushed up against the walls, leaving an open space in which to bram. The bram consisted of a stamping dance to a variety of beats. Hips and bellies gyrated, shoulders swung, and arms flung about with abandon, resulting in flowing contortions of the body while the legs kept up a rhythmic bram! bram! bram! Music was supplied by any combination of two or three of the following: drums, accordions, banjos, guitars, mouth organs, forks pulled across graters, pint bottles tapped against each other, comb covered with soft papers, brooms struck on the floor…liquored flowed: rumpopo, spruce, and wines made from cashews, blackberries, oranges, craboos, or ginger…Bram continued for two full days without stopping. (1978)

This snapshot of Christmas Bram is almost identical to the historic Bram that was described by the community elders in Gales Point Manatee. Bolland’s (2003) historical analysis of African cultural continuities in Belize also supports Stuart (1978) and Greene and Rubenstein (1991) observations. The Christmas season was an opportunity for African groups and families to re-unite during slavery served as an outlet for cultural expression. Accounts of the atmosphere during the Christmas season are provided below.

1809

The members of several African tribes, again met together after long separation, now form[ing] themselves into different groups, and nothing can more forcibly denote their respective cases of national character than their music, songs and dances. The convulsed rapid movements of some, appear inconceivably ludicrous;…The endurance of the negroes during the period of the holidays, which usually last a week, is incredible. Few of them are known to take any portion of rest for the whole time; and for the same space they seldom know an interval of sobriety. It is the single season of relaxation granted to their condition; (Bolland, 2003)

The Christmas season served as the greatest opportunity for communal recreation among slaves between long periods of working at timber camps (Bolland, 2003). Other accounts demonstrate the endurance of this tradition towards the end of the 19th century.

1883

At Christmas when the season’s work…was over, the slaves were allowed from three weeks’ to a month’s license to enjoy the pleasures of town in Belize…These [slaves] congregated in several bodies, and followed the African rites they had brought with them…Amongst other questionable results deducible from slavery-times this of keeping festivity going all night as well as all day, clings to the celebration of the Christmas holiday still. Music and dancing and the extravagant consumption of gunpowder by discharging it from their shot-guns, were common to all the tribes (Bolland, 2003).

Outside of Belize City and Gales Point Manatee, the survival of the Christmas Bram in other historically Creole villages remains to be explored. During informal conversations with persons from the Belize River Valley communities over the years, Bram was an integral part of the Christmas traditions in places such as Burrell Boom and Rancho Dolores. The survival of a version of Bram is also believed to still be practiced in Georgeville in the Cayo District. These mentions warrant further research to see if there is indeed any continuity.

BRAM IN GALES POINT MANATEE

Manzanares describes Bram as “a spree traditionally done during the Christmas season. It is an exodus of people dancing in the streets from one house to the next, the goal of which is merry-making by singing, dancing and playing music at each house as a sign of good cheer”, (n.d.). This description appropriately summarizes the practice of Bram in Gales Point Manatee. Similarly to Belize City, community elders note the festivity has much changed throughout the generations. In general, there has been a decline in cultural practices and traditions such as farming, dorey making, story-telling etc. in the community. Two of the main factors cited during Hyde’s research are reminiscent of Belize City circa 1989 – the emigration of community members and a general disinterest by the younger generation to engage in cultural activities and learning.

The term ‘bramming’ is used to the describe participants involvement in the various activities of Bram – merry-making, dancing, singing and feasting (National Kriol Council, 2011). On the surface, Bram appears to still be a strong communal tradition reflected by the large number of participants during both days of the celebration. However, there are certain factors that may work against its continuity in the long run.

The brokdong rhythm is the sound of Bram. As Manzanares stated “though the brokdong can occur without the Bram, the Bram cannot occur without brokdong music” (n.d.). Indeed, music forms the heart of the celebration, as the sounds signal to the community that the celebration has begun. It is the unifying element of the celebration. The drummers play the traditional call-and-response folk songs to the brokdong rhythm (National Kriol Council, 2011). As vital as the music is to the tradition, it represents an as aspect of the tradition in need of safeguarding. “Over the years, the brokdong genre has experienced a lull in its popularity among the youth” (Manzanares, n.d.). The unique sound of the brokdong was created through a mixture of household implements and musical instruments. Manzanares recalls, “the musical instruments that they use to use in the first instant of the bram, they use to use things outta the house, I remember as a child they take the comb and they put like a lil silver paper on it, and they blow it and the silver paper they got out of ching gum, and they blow that and make music, they use to have the grater and you get a fork and you rub that together…that make music” (2014). Today, this is rarely seen and is a practice that would be found among the community elders only. There is one man, an elder in the village, who still brings out his grater during the bram. The sound of the celebration has changed over the years as certain traditional musical instruments are no longer a part of the celebration.

According to Emmeth Young, lead musician during the celebration, “in ancient times, earlier times, we use to use the accordion because we had people here that played the accordion, and the banjo,” (2013). He elaborated that this loss in the music is related to the passing away of elders who possessed the knowledge and skills to play the traditional instruments. There is also little to no interest by the younger generation or youths to learn these skills from their elders. Young himself acquired the traditional knowledge from community elders to make the sambai drum; a drum unique to Gales Point Manatee and also used in the celebration. Today he is one of the few remaining musicians in the country with the traditional knowledge and craftsmanship skills to make the creole drums. He established the Maroon Creole Drum School in the village when he “realized that the drumming tradition in the village was dying: he made drums, offered free lessons in drum-playing…and revived the Sambai amongst the young people,” (Hyde, 2012). The drum school was open in Gales Point Manatee for several years before relocating to Punta Gorda Town. Today Young and his musicians incorporate the djembe and gombay drums, both adopted from other Creole communities in the celebration.

The sambai, a traditional dance that was jumped by African descendants is a fertility dance originally held during the full moon. It is danced in the form of a ring around a fire, which is seen as a symbol of virility (Hyde, 2012). In the past, the sambai was done from the month of November leading up to the days of the Christmas Bram (Gentle I. , 2014). Today the sambai has merged with the Bram and is mainly done during Christmas night. This shift has changed the cultural landscape in the community as Ms. Estelline Welch, a community elder shared, “things use to be brighter when we were younger because the time they would have a little dance, there would be sambai every night,” (2013). Some elders attribute the decrease in the occasions of the sambai to the emigration of Emmeth Young and other musicians.

One new factor that may pose a challenge in the continuity of the celebration is the introduction of new religious denominations. During festivities in 2013, persons carrying out the inventorying of Bram noted that persons affiliated with a certain missionary group appeared to be discouraging persons from participating in Bram. This missionary group is recent to the village and in follow-up interviews it was confirmed that there has been efforts discouraging community members from participating in the Bram. While the reason behind this was not clearly stated, it can be speculated that as a secular tradition participation would not be welcomed by some church groups. Mr. Raymond Gentle, an elder and participant of Bram, believe that this would not affect the continuity of Bram as the community will not listen to the message from the missionaries and Bram will continue as it has throughout the generations (2014).

There are many other aspects of the Christmas Bram that has changed over the years but discussion of all aspects would require an extended paper on the subject alone. Culture is dynamic and echoing on Van Zanten’s statement with each generation a tradition will be transformed to suit the needs of that generation. For this purpose of this paper, what has been presented is not just the transformation of the tradition of Bram, but the identification in a gap within in its continuity. As will be discussed in Carnaval, what happens when there are no persons remaining with the traditional knowledge to perform the music? Will the tradition shift to using recorded version? The impact of new religious movements remains to be seen. Carnaval in Caledonia has faced similar challenges and may provide us with a glimpse into future of Bram if the impact of these challenges begins to outweigh its cultural transmission.

Figure 3: Emmeth Young (far left) and other drummers performing during the Christmas Bram. © Institute for Social and Cultural Research/NICH (2013).

Figure 4: Bramming taking place outside a home. © Institute for Social and Cultural Research/NICH (2013)

CARNAVAL IN NORTHERN BELIZE

Carnaval was brought during the migration of Mestizo and Maya Caste War refugees from the Yucatan, Mexico (Briceno, 1981). Carnaval is a pre-lenten festivity in which dancers go throughout the village performing various dances such i.e. la cinta (maypole), el torito (the little bull) etc. familes who pay a small fee to see the dances. While Carnaval is perceived by many as a Maya/Mestizo tradition, Cocom (2012) suggests that Carnaval in Belize is of mixed origins with Maya, African, and European influences. Two of the sources that shed some historical insight into the tradition are by Jaime Briceño and by Roman Magaña. Briceno’s (1981) article entitled, “Carnaval in Northern Belize” highlights role of Carnaval and its decline in communities. Carnaval is described as “the last fling before Lent, a period of forty days during which no form of entertainment could be held and in which those days were religiously observed” (Briceno, 1981). It was a recreational, cultural, religious and economic event but it also served as an outlet for social expression (Briceno, 1981). It was during this time that social issues affecting the community would be brought out in the open using comedy and fun. Each year new songs would be created reflecting the social atmosphere at the time.

Briceno’s article also addressed the discontinuity of the practice across much of northern Belize by 1981 with the main reason being “modernization”. In Roman Magaña’s (1991) unpublished manuscript,”Carnaval in Progresso” he describes the various components of Carnaval and reiterates Briceño point. The village of Progresso is within close proximity of Caledonia and shares a similar heritage. By 1991, the practice had severely declined in the community and as a result of “development” and “technology”. Unlike today, Carnaval was historically a tradition organized and led by men. However, with the establishment of the sugar factory in neighboring Libertad, many of the men began working there were no longer available to organize Carnaval (Magana, 1991). As persons in the community did not take up the role of organizing Carnaval, this greatly contributed to its decline.

Magaña also notes the change in the Carnaval music which consisted of live performances by musicians had begun to be replaced by recorded versions. Whether this is due to a lack of musicians in the community or a matter of convenience is not stated. Today, many of the cultural performing groups and schools that host Carnaval activities use a recorded version. In the village of San Jose/San Pablo, Corozal there is still one remaining group of musicians known as Banda Maya, that play the instrumental music that accompany the Carnaval songs and dances.

Carnaval in its traditional form as a communal tradition has disappeared from most of Northern Belize. Apart from Caledonia, the festivity has survived on the island town of San Pedro, Ambergris Caye. The version practiced is a much more modernized than described by Briceño (1981) and Magaña (1991) but there are still key traditional elements present. It illustrates the point that culture is dynamic as the practice has changed to meet the needs of cultural actors involved and its audience.

Caledonia is perhaps the last place where it remained as a communal tradition. However, like Progresso the community faces various factors that have put into question its continuity. While this remains to be determined, some of the main factors will be discussed.

CARNAVAL IN CALEDONIA TODAY

Like the Christmas Bram, Carnaval was once an integral part of the communal traditions practiced in Maya/Mestizo villages across northern Belize. Like Bram this tradition resonated within communities as part of a shared cultural heritage. In the community of Caledonia, Carnaval was part of the rich traditions celebrated. While the date of the establishment of the village is not easily identified, it is certain that Carnaval has been celebrated in the community for more than 50 years as Doña Ernestina Moh represents two generations of the tradition in the village. Doña Ernestina inherited the tradition from her father, who also organized the celebration during his time. She begun participating during her late teenage years and today at 76 years of age has organized the celebration annually up to last year – 2014.

Community elders recall that Carnaval would be organized by various families simultaneously in the village. Therefore multiple groups would be doing Carnaval dances and performances throughout the village. Today, Carnaval is still a community tradition as various families support it by requesting that Carnaval dances are performed at their houses. Of interest, is that most of these households are either elders, or families with elders who are brought out during that time to see the dances.

Through the information collected by interviews, factors given by community members to explain this decline center on the introduction of other religious groups in the community, and a lack of interest by the younger generation of today. Additionally, there is also a perspective in the community which holds Carnaval as a family tradition belonging to Doña Ernestina’s family.

Carnaval has always been a tradition connected to Catholicism because of its connection to the Lenten Season. However, today, Carnaval cannot be considered solely a religious tradition, but rather a cultural festivity. Carnaval participants engage in the revelry of the season (which includes singing, dancing and drinking) as it is perceived as the final days for merry-making before the observance of Lent. The burning of Juan Carnaval, an effigy created to represent the wanton revelry of the season is burnt on the night before Ash Wednesday marking the end of the Carnaval season (Magana, 2015). On Ash Wednesday morning or evening, participants received their ashes and commenced the observance of Lent. Carnaval participants note that the Catholic Church has always been accepting of their participation in Carnaval, however it is other religious denominations that have impacted the participation of others.

Some of the Carnaval dancers, mainly girls have joined other churches in the village and participation in Carnaval is not tolerated according to those other church’s beliefs. As a result, several dancers have stopped participating in Carnaval. As it pertained to the beliefs system of the other churches, Margarito Medina (2011), one of the main Carnaval performers remarked, “It is because that is the rule in their religion…you have to have fun for a while, but they don’t, they see it [Carnaval] as something demonic, the devil’s game”. He further stated about Carnaval, “yes it’s bad but only for a while, then you go to church, pray and receive Holy Communion then it’s okay”. Doña Ernestina Moh, who was present at this interview stated, “but at the same time, it’s culture”. This statement support’s Briceño point that persons did not solely participate in Carnaval for fun, “but also to keep alive their culture and maintain a sense of continuity with the past” (1981).

Figure 5: Performance of “El Torito” dance in Caledonia. © Institute for Social and Cultural Research/NICH(2014)

It is easy to see the reasons that the tradition would not be supported by some religious groups. The three days of Carnaval, immediately preceding Ash Wednesday represent the climax of the season and is therefore celebrated to the fullest by participants. As observed, some dancers consume alcoholic beverages and Juan Carnaval himself is displayed with a cigarette in his mouth and two empty bottles of rum on both sides of where he is seated. Another point for negative association is the physical representation of the El Diablo (the Devil) during the festivities. During the festivities, one of the participants is clothed in red, wearing a horrific mask, representing the Devil. The Devil is used during Carnaval to symbolize that evil is lurking in the community and as a form of social control to scare little children and that they be of good behavior.

In the past, Carnaval was a communal tradition that helped to keep alive the community spirit and cultural unity throughout Northern Belize (Briceno, 1981). Today in Caledonia, one family has organized the celebration for the past decade. The survival of the tradition in Caledonia, can be attributed the strengths found in family traditions. Almost every aspect involved in organizing and performing Carnaval is distributed throughout the family. When asked about their participation, the general response from participants is that it is a part of their tradition. For Doña Ernestina, tradition and culture is at the heart of her continuing Carnaval in her elderly years. However in 2014, she announced towards the end of the celebration that it was her last. Simply, she was old and tired and no longer had the strength to carry on the tradition like previous years. Of all her children and grandchildren that participated, no one was eager to take on the mantle of carrying on the organizing of the celebration.

A few years ago, when asked who would continue the celebration if Doña Ernestina was able to no longer, Medina stated, “I don’t know who” (2011). Other community members have remarked that Carnaval in Caledonia a family tradition rather than community cultural tradition therefore is little chance that someone outside of Doña Ernestina’s family will resume the tradition. Over the course of year, several of the younger family members who had seemed promising in leading the tradition have emigrated to other communities either due to work or romantic relations.

Figure 6: Ms. Ernestina Moh (far left) and some of her family members who participate in Carnaval. © Institute for Social and Cultural Research/NICH, 2014.

Another aspect of the celebration of urgent concern is the Carnaval music. Similarly to the Gales Point Manatee, many of the musicians in the community have passed away without passing on their knowledge and skills to the other persons. There is one remaining musician, Octaviano Pott who plays the Carnaval music, using his accordion. Pott mentions that there was a band of musicians in Caledonia during the 1960’s but after the members became too old to perform that marked the end of it in the village (2015). Sadly, their music was never recorded. Pott has been playing the music for Carnaval using the same accordion for the past forty years. He wishes that the younger generation would become more engage in the tradition. He recognizes the importance of the tradition but fears he would not be able to teach others how to play as he learned only ear.

Without any of the family members taking on the necessary leadership role to organize Carnaval, 2014 may have been the last communal version of the tradition performed. However, this may not be the end of Carnaval in Caledonia. From November 2011 – February 2012, NICH through ISCR facilitated a cultural education program at Caledonia Roman Catholic Primary School where Carnaval was offered as one of the elective options students could choose. Doña Ernestina taught four of the Carnaval comparsas to students that were enrolled in the program. At the end of program, fourteen of the initial group of sixteen students completed the first phase of the program and participate in a public Carnaval presentation at the school. The long term impact of this program remains to be seen and a separate discussion of the cultural education program is needed.

CURRENT SAFEGUARDING MECHANISMS

There are safeguarding initiatives that have been taking place at the community level to ensure various Creole cultural forms continue. Young’s Maroon Creole drum school, although no longer located in Gales Point Manatee, continues to be a mechanism for the transmission of craftsmanship skills and traditional knowledge opened to any interested individual. The National Kriol Council has also been active in promoting the Creole culture through various publications, capacity-building community projects and educational programs within Creole communities to foster cultural transmission. Myrna Manzanares has also formed a cultural dance group that performs various traditional kriol dances including the sambai.

While Carnaval might no longer a communal tradition on mainland northern Belize, the dances and songs are still alive as a result of various initiatives by community performing groups and schools. There are several Mestizo cultural dance groups from both the Orange Walk and Corozal district that incorporate Carnaval presentations into their performances. These groups represent an excellent medium for cultural transmission between generations as they are normally led by older community members who teach the songs and dances to youths. Additionally, several schools have incorporated a performing arts component in the form of after-school dance clubs where students are taught the dances and song. School also present Carnaval dances as part of highlighting the Mestizo culture on cultural days. The work of the Houses of Culture in leading community retrieval projects must also be acknowledged. Both the Banquitas House of Culture in Orange Walk and the Corozal House of Culture has organized Carnaval presentations and exhibits to engage the community.

Additionally, the information collected during the pilot project is being used by ISCR/NICH to produce various educational materials (i.e. exhibit, videos, and posters) about Carnaval, Christmas Bram and the other cultural celebrations that were inventoried. These will be available for the community, schools and the wider public.

CONCLUSION

This paper has examined some of the factors of cultural change in the celebrations of Bram and Carnaval in Belize. These two celebrations were the most appropriate case studies to analyze the initiatives of safeguarding ICH and to examine cultural change because these practices were viewed as ‘at risk’ cultural celebrations during the inventory process. This paper examined the historical context of these celebrations, mapped cultural changes, and attempted to develop a tentative analysis of how communities are perceiving the continuity of the celebrations.

It showed that while there is some level of safeguarding, there needs to be more strategic and active initiatives to encourage communities to safeguard their respective cultural celebrations. On the national level, the implementation of the ICH Convention has so far created a network of cultural stakeholders, bearers of ICH, cultural activists and organizations who are working towards developing both short-term and long-term safeguarding mechanisms. Many cultural bearers have also participated in the development of a National Culture Policy (NICH) which presents a new concentrated interest by stakeholders to collaborate on how cultural practices such as Bram and Carnaval can be safeguarded. Going forward, there will be a need for researchers and cultural stakeholders to examine the best safeguarding practices and assess the outcomes. As indicated in the introduction; however, the continuity of these two celebrations will depend on how communities respond or adapt to contemporary processes such as new religious movements, disinterest by youths, emigration of community members, and globalization among other factors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

This research was made possible through the Institute for Social and Cultural Research (National Institute of Culture and History), and key partners UNESCO and the Japanese Funds-in-Trust. The participation of communities of Caledonia and Gales Point Manatee was crucial to the success of this research project. Community members that provided invaluable information over the years include Doña Ernestina Moh and family, Augusto Olivarez, Myrna Manzanares, and Emmeth Young as well those interviewed. The contribution of the ICH Working Body must be commended for their tireless efforts during the inventorying project that at times involved travelling to unfamiliar communities, working during Christmas Holidays, and working long hours for the purpose of safeguarding ICH. Individuals that contributed to the development of this research paper include Rolando Cocom who acted in the roles of co-researcher during early field work and editor of this paper; Giovanni Pinelo who acted as co-researcher and whose insight helped to position first version of this paper presented and Linette Sabido who translated many of the interviews for the purpose of this research paper.

Endnotes:

- Hereafter referred to in this paper as the ‘ICH Convention’ or ‘Convention’.

- The Banquitas Action Plan was drafted on the 9th October, 2013 at the Banquitas House of Culture, Orange Walk Town, Belize. The action plan was drafted with the assistance of UNESCO facilitators as well as participants of the workshop and NICH personnel. A copy of this action is available at ISCR, NICH.

- See Cocom (2012) paper on Carnaval in Caledonia: A Preliminary Ethnographic Profile of Ethnographic Practices published in the Research Reports on Belizean History and Anthropology Vol. 1.

- See Manzanares and Cocom, 2015 in this volume.

- “ching gum” means “chewing gum”

- In this context comparsas refer to the songs and dances of Carnaval.

REFERENCES:

- Bolland, O. N. (2003). Colonialism and Resistance in Belize: Essays in Historical Sociology. Benque Viejo del Carmen: Cubola Productions.

- Briceño, J. (1981). Carnaval in Northern Belize. Belizean Studies , 1-7.

- Cocom, R. (2012). Carnaval in Caledonia: A Preliminary Ethnographic Profile of Carnival Practices. Research Reports in Belizean History and Anthropology. 1. Belmopan: Institute for Social and Cultural Research.

- Gentle, I. (2014, June 12). (M. Manzanares, & P. Pelayo, Interviewers)

- Gentle, R. (2014, June 12). (M. Manzanares, & P. Pelayo, Interviewers)

- Greene, L. A., & Rubenstein, J. (1991). Christmas and Bramming in Belize City. Journal of Belizean Studies , 19 (2/3), 31-39.

- Hyde, R. (2012). Stone Baas People: An Ethnohistorical Study of Gales Point Manatee Community. Journal of Belizean Studies Vol. 31 No.2 , 8-66.

- Magana, R. (2015, February 26). (P. Pelayo, Interviewer)

- Magana, R. (1991). Carnaval in Progresso.

- Manzanares, M. (2014, December). (P. Pelayo, Interviewer)

- Manzanares, M. (n.d.). All to the Sound of Brokdong. Retrieved June 20, 2014, from Belizean Journeys: http://www.belizeanjourneys.com/features/brokdong/newsletter.html

- Medina, M. (2011, November 30). (P. Pelayo, & R. Cocom, Interviewers)

- National Kriol Council. (2011). Bram and Brokdong. Retrieved June 23, 2015, from National Kriol Council: http://nationalkriolcouncil.org/the_culture/dance

- Olivarez, A. (2011, December 08). (R. Cocom, Interviewer)

- Pech, A. (2011, December 01). (R. Cocom, Interviewer)

- Pott, O. (2015, June 13). (G. Pinelo, Interviewer)

- Statistical Institute of Belize. (2013). Belize Population and Housing Census.

- Stuart, G. (1978). The Christmas that went before. Brukdown Magazine (No. 2), pp. 10-11.

- UNESCO. (2013). Second Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) Community-Based Inventorying Workshop. Retrieved June 17, 2015, from

- UNESCO: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/unesco/events/all-events/?tx_browser_pi1%5BshowUid%5D=16305&cHash=8c23016e47

- UNESCO. (2014). What is Intangible Cultural Heritage. Retrieved June 15, 2014

- UNESCO; ACCU. (2006). Expert Meeting on Community Involvement in Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage: Towards the Implementation of the 2003 Convention Report. Tokyo: Intangible Heritage Section, Division of Cultural Heritage, Sector for Culture, UNESCO.

Van Zanten, W. (2004). Constructing New Terminology for Intangible Cultural Heritage. Museum International . - Welch, E. (2013, December 25). (G. Pinelo, S. Solis, & M. Manzanares, Interviewers)

- Young, E. (2013, December 26). (M. Manzanares, S. Solis, & G. Pinelo, Interviewers)

How to cite:

Pelayo, P. (2015). Safeguarding our cultural heritage: Addressing change and continuity of Bram and Carnaval in Belize. In N. Encalada, R. Cocom, P. Pelayo & G. Pinelo (Eds.), Research Reports in Belizean History and Anthropology (Vol. 3, pp. 91-102). Belize: ISCR, NICH. Retrieved from: [Insert BHA URL]

Download full article here!