Cutlural Change in Gales Point Manzanares Cocom BAAS Tag Culture

Cutlural Change in Gales Point Manzanares Cocom BAAS Tag Culture

Cultural change in gales point manatee: Auto-ethnographic reflections from a community member

By Myrna Manzanerez and Rolando Cocom

This report seeks to present an interpretive perspective of cultural change in the African descent community of Gales Point Manatee, Belize. The paper is empirically based on the biography and observations of Myrna Manzanares (co-author) who has participated in many cultural research and initiatives in the community. The themes addressed include language, spiritualism, social mores, music, dance, and social problems. One of the significance of this report is that it provides readers with an introductory text to the cultural practices and cultural changes occurring in the community. A second importance of this research is that it may be useful for future studies seeking to understand the processes of cultural change and cultural identity in the community and by extension in Belize.

INTRODUCTION

The analysis of cultural change in Belize has been a field of concentrated interest among scholars from a variety of disciplines, including history, sociology, and anthropology (Bolland, 2003; Cocom, 2013; Iyo, 2000; Shoman, 2010; Wilk, 2002). This interest is also reflected in the public sphere where many cultural groups, organizations, and initiatives (e.g. “Local Cultural Groups”, NICH) have been established to address how Western influences (e.g. capitalism , technology, and religious movements) are impacting the way cultural festivities, language, and local cuisines, among other cultural forms, are practiced in Belize.

In the last few years, there has been an initiative spearheaded by the National Institute of Culture and History (NICH) to sensitize communities about the importance of safeguarding Belize’s intangible cultural heritage. One of the maxims of the initiative is to place community members at the forefront of how cultural practices are documented, represented, and safeguarded for future generations.

While we agree that culture is a dynamic and ever changing set of overt and covert practices, the analysis of ‘cultural change’ in the social sciences is considered a useful field towards understanding the processes which shape current group identities and contemporary social contexts (Bolland, 2003; Iyo, 2000). The analysis of cultural change allows us to interrogate the historical and social forces at play in communities and to address how these changes have been interpreted and represented in public and academic discourse. In Belize, the processes of cultural change among African descendants in particular continues to be debated in creolization studies and African diaspora studies (Bolland, 2003; Iyo, 2000; Macpherson, 2003) which provide us various models of comprehending cultural change from anthropological and historical perspectives.

Without pursuing an in-depth analysis of the existing literature, it is hoped that this auto- ethnographic report will contribute to the project of analyzing the cultural changes in the village of Gales Point Manatee (GPM), Belize. The paper is empirically based on the biography and observations of Myrna Manzanares (co-author) who has participated in many cultural research and initiatives in her birthplace of GPM (Hyde, 2012; Manzanares, 2006; Wade, Herrera, Woods, & Manzanares, 2005). The research is viewed as an interpretive contribution to the field of cultural change and may be useful as an introductory text to GPM and as an ethnographic source for future research. It presents a narrative that is rooted in Manzanares’s individual experience, intellectual knowledge, and shaped by her current concerns and aspirations as a researcher and a cultural activist.

The function of the co-author (Rolando Cocom) in this report was to organize the academic frame from which to present this narrative, a version of which was presented at the 6th annual Belize Archeology and Anthropology Symposium (BAAS, 2014). In order to retain as much as possible the perspective of Manzaneres’s narrative, limited editing was carried out on her text. This allowed her voice to be more pronounced in the way her narrative was stylized and articulated. However, the role of the co-author (Rolando Cocom) also included providing a brief analysis on the historical background of GPM, the research methods, and the introductory notes to the Manzanares’s texts, along with providing some concluding remarks.

As indicated, the following section provides a short historical background GPM.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

In order to understand the development of GPM, we must acknowledge that the presence of Africans and African culture in Belize was due to the forced migration and enslavement of Africans in Belize. Africans were enslaved to labor in the timber industry and generally comprised the majority of the population from the 18th century to mid-19th century (see Iyo, 2000).

However, contrary to the narrative popularized by Emory King (1999), slavery in Belize was not a ‘family affair’. The resistance to enslavement came in various forms. For example, there were armed revolts (1765, 1768, 1773, and 1820), ‘runaways’ (physical escapes from the settlement), and the pursuit of legal redress (Iyo, 2000; Shoman, 2010). There were also less open forms of resistance: back-chatting, abortion, and working as little as possible (Iyo, 2000). It is also known that there was a high rate of runaways throughout the period of enslavement in Belize (Iyo, 2000).

Many of those who escaped fled across to the Spanish settlements in the northern and southern frontiers (Bolland, 2003; Iyo, 2000). However, there were also those who resorted to the practice of maroonage (Bolland, 2003; Hyde, 2012). Maroonage refers to the practice of resisting enslavement by fleeing the control of the colonial authorities or ‘slave masters’ to live in self-sufficient communities in the hinterlands. It is a practice evident in most enslaved societies of the Americas (Price, 1996).

Based on textual and oral history, Hyde (2012) has argued that GPM located at the tip of the southern lagoon in the Belize District was a secondary settlement established by maroon Africans and their descendants. She explains that there were once various maroon communities whose members frequented and eventually resided in GPM around the late 1700s and early 1800s. Such nearby communities are said to have included settlements at the Sibun River, Runaway Creek, Mullins River and Main River (now called Manatee River by community members). Family names with ties to Gales Point are said to include the “Welchs, Slushers, Garnetts, Myers’s, Gentles, McCords, Andrewins, Jenkins’s, Flowers’s, Timmons’s, Bowens, Goffs, Abrahams, Wades, Westbys, Baileys, Youngs and McDonald” (Hyde, 2012, p. 21).

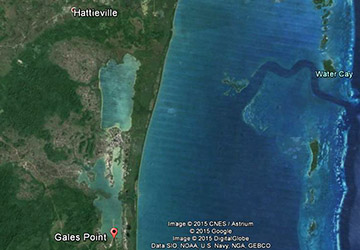

Figure 1: Outline of Belize District showing Gales Point Manatee (Courtesy Google Earth).

Due to its geographic location, African cultural continuities have been more evident in GPM than other locations in Belize. For example, Iyo, Froyla, and Humphreys (2007) have stated that “apart from Gales Point Manatee, no other Creole community in Belize has an African type drum” (p. 28). For most of its history, GPM has been known as location where African cultural practices such as ‘Sambai’ (a fertility dance), ‘Negromancy’ (spiritualism and supernatural practices), Christmas Bram (a festivity), and folklores have been practiced (Hyde, 2012; Iyo et al., 2007). However, such cultural practices are now said to becoming less and less practiced (Hyde, 2012). The most recent census report places the population at 296 persons (SIB, 2013). The census also indicates that the population is organized in about 72 households. At present, there is a road network linking the George Price Highway and the coastal road which provides for road transportation to GPM. However, the accessibility to and from the community remains limited (Hyde, 2012). Out-ward migration, unemployment, and drug use (Hyde, 2012) are also cited as factors which contribute to an observable change in the cultural practices of the community which are furthered examined in this paper.

RESEARCH METHODS

The research method of this paper is located in the methodological epistemology of qualitative research (Denzin & Lincoln, 2005). The paper is specifically conceived as an auto-ethnographic research in which researchers turn the analytic lens on themselves “to write, interpret, and perform their own narratives about culturally significant experiences” (Chase, 2005, p. 660). In this case, the narratives are drawn from Myrna Manzanares on the topic of cultural changes in GPM.

The narratives of Manzanares are based on her life-history, experiences, observations, everyday talks, and knowledge of GPM. She provided Rolando Cocom (co-author) with the manuscript of her perspectives on the cultural change in GPM. Her manuscript was then transcribed and edited. She also had the opportunity to review the drafted article and provide feedback for its finalization.

The value of this form of research is that it provides both biographic insights and interpretive perspectives on the topic (Chase, 2005). It allows Manzanares to project her voice both as a researcher and participant of the community. The degree of trustworthiness of this form of research is that it co-relates with existing literature (Hyde, 2012; Iyo et al., 2007) and more importantly is that it aims to present interpretive perspectives instead of attempting to explain them (Chase, 2005). The paper thus resists the objectification of each and every statement made by the narrator which allows the narrative to remain open to multiple interpretations and further analytical inquiries.

BIOGRAPHIC POSITIONALITY

In order to better appreciate the succeeding section which focuses almost exclusively on the processes of cultural change, it is useful to illuminate the position from which Manzanares speaks. This section is based on a biographic text by Manzanares.1 The biography interweaves her individual experiences with that of her social experiences in GPM. The biography which was written in the first person is as follows:

I was born in 1946, in Gales Point Manatee, a peninsula at the southernmost village in the Belize District. The village was almost surrounded by two lagoons, which we referred to as the front lagoon and back lagoon. My village was only about a mile long back then, with one main street. In most instances the homes were on one side of the road, facing the front lagoon. Looking back, I can honestly say that I had a very rich childhood. It was rich in the sense that I grew up in a large extended family, and a small community where everyone looked out for each other. My mother was the craft instructress in the village and she was well respected by all, so if I did anything out of the way you know that she would know. I had several grand aunts, and grand uncles and many more cousins from those sides. My grandmother and grandfather were alive back then and my grandmother had a shop that catered to the villagers on our end of the village…

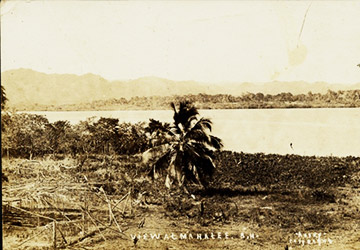

Figure 2: View at Gales Point Manatee, circa. early 1900s. Courtesy, Eric King Collection , NICH

In my village we jumped the Sambai during the period of the full moon, we brammed during the Christmas season, we had wakes at funeral, sung folk songs and did all of the traditional things typical of the Belize Kriol in those times. A sense of culture togetherness, and inclusiveness typical of true community spirit – became a part of my psyche inherited from my childhood experience.

I left Belize in 1965 to join my family who had migrated to the United States (US) after Hurricane Hattie (which occurred in 1961). In the US my family still maintained that spirit of community because the elder heads of the family were still alive. I missed the freedom of my country, and felt that I was beginning to lose some of the cohesiveness that kept our family together. The overwhelming culture of the US was taking a toll on our young members of the family. All the stories my grandfather used to tell us were getting lost so I began to write them down. I knew this was the medium that I could use to engage any audience and share elements of my culture.

Although life was good in the US, I was always haunted by the thought that I was losing so much of who I was. In 1986, I gave up my home, my job and came home with my 8 year old and settled back home as though I had never left. I became involved with cultural activities, -storytelling, plays, Queen of the Bay pageant, 10th of September parade, etc. I still didn’t feel that satisfied that I was tapping into the culture.

Then one night I saw a performance by Lila Vernon and her dancers and I heard her sing her now very popular song “Ah wahn no who seh Kriol no gat no kolcha”. When I heard this song and saw the reaction of the audience I knew that there was work to be done and that it must be done to stimulate pride in the Kriol culture.

I found people who were as concerned as I was about the Belize Kriol culture and Language and in 1995 because of those concerned people The National Kriol Council was incorporated as a not-for profit cultural organization.

NARRATING CULTURAL CHANGE

The following text was drafted by Manzanares to describe the cultural changes she has witnessed in GPM. She pursues a narrative approach in her description, assuming the reader has little knowledge of the history of GPM. Her account attempts to describe the change across three generations. She describes the first generation as “those days” or the “old days” which are based on the narratives and experiences of her parents and grand-parents (the early 1900s). She then describes the “not so olden days” or the “second generation” which is when she was growing up (1940s-70s). The third period described are referred to as “today” or “this generation” (1980s – present). While the narrative is underdeveloped on some topics, it provides an insightful set of perspectives. The narrative is as follows:

Gales Point Manatee is a Kriol village with a strong African presence.2 I was born in this village and I have been in love with it since I was a child. It is believed that somewhere between the late 18th and 19th century, runaways, enslaved people established this village. The African traditions practiced in this village are an integral and everyday part of its lifestyle. There are so many things I could remember in my village when I was a child that no longer exists today.

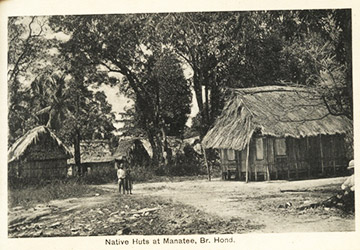

As a child I could remember that any adults of the village had the authority to discipline any children. It surely was the community raising the child. There existed a high level of respect for others especially the elderly. All the houses in this village were made of thatched roofing made of bamboo and cohune. The elders tell you that these types of houses were cooler and healthier. The flooring were plastered with mud, similar to our African ancestors, and the walls were colored with newspaper and magazines for wallpaper.

In those days there were no cars and only a few people had bicycles. People usually travelled by dugout dories, or sailing boats. Of course dorey building was a part of our tradition, and the village had specific people who built the dories, just like other Kriol communities. From children were small they were able to make dories. Some of the fun dories they made were from the dry coconut husk. They cleaned it out and put in a paper sail. These were fun wholesome activity as they sailed their boats in the lagoon. The village had two lagoons and children were in them from a young age.

Figure 3: Houses in Gales Point Manatee, circa. early 1900s. Courtesy, Eric King Collection, NICH

One of the most important experiences in my life in the village was school. I was a rebel (mischievous child), but the teachers never gave up on me. The police, the nurse, along with the teachers were all important parts of the community. They lived in the village and the children respected them.

One thing that can definitely be said about Gales Point was that family traditions were transmitted to children in the by gone years, especially those of the Sambai. We grew up to believe it was a fertility dance, no explanations, just that. Before the dance begun, a huge fire made of pine wood was lit and the people would gather around the fire, and the drums would be beating until individuals began to dance. They would dance around the fire and pull out someone else to replace him or her. The manner in which they indicated their dance partners is with subtle sexual undulations. The dance was only done by the adults.

When the dance was done there would be a large fire and the drums beat while individuals dance around the fire and put out someone else to replace him or her. The manner in which they indicate to their partners is with subtle sexual undulations. The dance was only done by the adults.

Another festivity of Gales Point is the Bram which is done around the Christmas time when the mahogany workers come from being away for 6 months. People gather and parade from house to house to bring cheer. At each house they are given something to eat and drink.

Story telling was also a special time for children and adults as well. Children would gather around to hear all kinds of story. Some scary and others just delightful; however, all the stories had some sort of a lesson. These stories were passed down from our African ancestors. I have found our stories were similar to stories from the Caribbean (p. 4). In my family, my grandfather and then my mother were storytellers. I have carried on this tradition and I am now Belize’s only international storyteller.

In Gales Point we had one family that we saw as a warrior tribe. They looked out for reach other whether they were wrong or not. It was a “touch one, touch all” moto like our African ancestors. They lived in one compound with different houses. Many families lived like this in the village in the old days but things have changed today.

The older folks in the village had many beliefs consistent with the African heritage. The people believe in negromancy, an “obeah” in the old days, just like the other black groups in Belize.3 This was part of the African belief system, as they saw the use of this as protection.

Another popular belief is holding what we call a wake for the dead. This is having the dead in the yard or in the house in an open casket all night and people would come to pay their respect to the person for the last time. There would be singing of hymns and drinking all night long and local food like johnny-cakes, powda buns, fry fish soup etc. People got a chance to see and talk to the deceased body. All this was to bring closure for loved ones and friends.

Another cultural belief was about people born with caul. This is when the child is born with the placenta covering the child’s face. These people are able to see spirits. My mother was one of these people and we experienced many times when she protected us when she saw “something”. As a child growing up we had many folkloric characters which we as children we just knew was true, because the elders told us about them.

For example, there is the Old Heg. This is a woman who turns into bird at night, who goes and sucks her victim. Then there was Tata Duhende a man with thumb and only four fingers. 4 When you see him you have to show him four fingers or he would cut of your thumb. You had the Warrie Master who protects the forest and the men who turned into animals. There were also Jako Laterns, a great ball of fire that would get you lost if you follow it.

In these not so olden days, children’s games were popular. You did not hear about fighting and killing. The games were fun and there was lots of laughter – unlike today, the unity and togetherness in neighborhoods no longer exists.

The Kriol language, which is much loved by most people, also went through its changes. In my time, you were not allowed to speak the language in school. The connotation was that it was a bad (or inferior) language. In fact, it wasn’t even considered a language but a dialect, with a pejorative connotation to the term “dialect”. English was the language. At that time there were no concept of English as a second language, and because we were a British colony, English was considered the only true language. Today Kriol is spoken and/or understood by the numerous cultural groups in Belize and friends who visit our shores are much better off when they learn this Belizean lingua franca. Kriol in Belize, for those of you who are not familiar with it, is one type of English-lexified Creole language of which there are 16. Thanks to the great work of Dr. Silvaana Udz and Yvette Herrera from the Kriol Language Projek, Belizean Kriol has been recognized as the true language that it is and not as a substandard variant to the official language.

Very famous in our language and culture are the Kriol proverbs used by the elders to send messages or give important information. For example, proverbs like “wan wan okro ful baaskit”, which means that one by one with persistence we will get what we aim for, or “when fish come from riva batam and tell you seh dat haligeta gat beli ayk bileev ahn” which means when an inside source tells you of something you should believe it.

Gales Point was a ‘meka’ for socializing with your two generations. People come from the city for sailing, socialization, and picnics and camped under the trees. During the holidays and the weekends the small peninsula was filled with people having a good time.

The second generation (my generation) continued on with many of the traditions of their parents, like the way children were raised. Of course, it was not done as strictly and consistently as their parents but values and traditions were still present. The concept of the community raising the child was still prevalent. In terms of the many different beliefs, some were continued but others were not as strong. There was the problem of out migration after Hurricane Hattie. Many people went to the United States. There were still similarities in values and tradition and the way in which children raised but not as strictly.

Today the village of Gales Point is no longer self-sufficient. The young people are no longer interested in the farming; fishing and the logging no longer exists. Unemployment is high and youngsters hang around smoking or stealing, youngsters who go to the city for further education or to find jobs, only come home on weekends or holidays.

George Street in Belize has always been a place where people of Gales Point stayed when the go to the city, from ever since. There was no gang culture as such, they were just a people of similar kind bonding together and looking out for each other. One of the reasons for violence by Gales Point descendants is that the Belize City people would always make fun of the people from Gales Point. As a group of Africans… they were darker in color than many of the people from the city who were lighter in color because of the mix with other cultural groups especially their British ancestors.

The youngster were called “Malanti Black Bod”.5 For the older generation, this was mostly ignored and the youngest would choose to excel in school, just to show that they were not less than the city. That is why we have persons like Sir George Brown who became the first Belizean chief justice. There were people like Lionel Welch, lawyer; Denzil Jenkins, top business man in the citrus industry, Louise Hendy and many other educators, Valerie and Marina Andrewin, nurses, Phillip Andrewin engineer, Roy Bowen Social Worker, and myself as a community clinical counselor. There is also Emmeth Young who is a young drummer who has been engaging the children in the African drumming. There is Janice Young, who is a well-known bamboo craft woman. There are also many more persons whom have migrated to the US who have elevated themselves in spite of some of the injustices they suffer because they were from Gales Point.

The younger generation today handled all these bullying and ridicule by fighting back. Some of them did not do as well in school so they smoked and became a part of the George Street gang, in some cases mainly for protection. The youngsters from Gales Point have established themselves as fighters, and all of them were attributed to the ‘George Street Gaza Gang’ where in many cases this was just by association. Like the warrior tribe in Gales Point, they protected and looked out for each other. These youngsters would go home to their peaceful village on weekends and holidays just to relax until they go back to the city.

Figure 4: Emmett Young training kids to make musical drums, 2014, Courtesy NICH

This generation of young people no longer fosters traditional beliefs. In a random survey conducted about ten years ago, the youngsters were asked what they felt about the belief and traditions that their parents grew up with. They said they did not believe in them and said they understood this was a form by which their parents wanted to control their children’s behavior. Today, traditional beliefs are not even thought of among the young persons with the era of technology.

Values and respect that were so high in the older days do not exist. Most youngsters have no respect for each other or their parents, especially the elderly, who set the foundation of the beautiful African village. It is a shame to see young men and women smoking marijuana in front of their children and parents. There are also cases with the children from the age of ten who have also begun smoking. No one tells them of the dangers, they see their parents dong it so it must be okay. The elders are always wishing for the old days back, or lamenting the fact that children have no respect for their elders. The parent’s language around their children is sometimes indescribable.

As I look back on the freedom and fun and sense of love and security I had as a child in my little village, it pains me now to see the total difference of the path the village has taken today. High rate of teenage pregnancy, drug use, sexual abuse, lack of community spirit and respect for each other that use to prevail all make the environment for growing up today almost unhealthy for the many children in the village. I truly wish that the community spirit, which helped to shape me as an individual, and made who I am today, would resurface in my village in which they will not be divided, no one would be excluded, and where people would continue to reach out and extend themselves for the benefit of all.

In spite of all these changes from one generation to other, there is a caliber of people that the village can be proud of, who did not only make a difference in their village, but in the country as a whole. There is a group of people who are looking critically on reversing the present trend of Gales Point by working with children of tomorrow, to make Gales Point gain back its original status.

CONCLUSION

This paper has attempted to describe the socio-cultural changes in GPM through the use of an auto-ethnographic narrative of a community researcher and activist. The paper described the changes across three generations. The topics addressed included language, spiritualism, social mores, music, dance, and social problems.

One of the significance of this report is that it provided readers with an introductory text to the cultural practices and cultural changes occurring in GPM. The research is viewed as a strategy for the safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage as it encourages community members to articulate their perspectives of their cultural heritage. Manzanares described her concerns about the impact that outward-migration, unemployment, and urbanization have on discouraging young people’s participation in specific cultural practices. Weary ofthe cultural changes which she narrated, Manzanares concluded by articulating her hope that the future generations may engage in the cultural practices which were familiar to her when she was growing up. This she claim will foster unity in the GPM.

A second importance of this research is that it may be useful for future studies. Researchers may also employ this report in further analysis of cultural changes occurring in GPM and by extension Belize. For instance, scholars of creolization may interrogate the use of the term “Kriol” as oppose to “Creole” in Manzanares narrative, asking “what does tell us about the current configuration of Creole representation?”. Scholars of African diaspora studies may interrogate the emphasis of “African heritage” where it is imperative to ask “if Creole identities are a mixture of European and African culture, why is there no mention of which cultural traditions are European in the narrative?”. These questions, among others, are important for future studies as academics and cultural activists continue to ponder upon the question of ‘who will define the Creole culture’ (Judd, 1990).

Notes:

- The text is edited from an interview transcript of an online magazine (see Manzanares, “Twenty Questions”, n.d.).

- The term “presence” is here taken to mean cultural heritage or traditions.

- Obeah is a form of African spiritualism which was outlawed in the settlement in 1791 (Iyo, 2000). The European settlers believed that it was connected with the resistance movements of the enslaved.

- Manzanares claims that the there is a difference between the Tata Dwende and Tata Duhende. Accordingly, the difference is that the Tata Dwende is shorter in height and is associated with Maya Mestizo culture. Whereas, she claims the Tata Duhende is tall in stature and of dark complexion.

- Malanti is the creole pronunciation of Manatee, see Hyde, 2012.

References

- Bolland, O. N. (2003). Colonialism and resistance in Belize: Essays in historical sociology (2nd rev. ed. ed.). Benque Viejo del Carmen, Belize ; [Great Britain]: Cubola Productions.

- Chase, S. (2005). Narrative Inquiry: Multiple lenses, approaches, voices. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (Third ed.). London: Sage Publications.

- Cocom, R. (2013). Carnival in Caledonia: A preliminary ethnographic profile of carnival practices Research Reports in Belizean History and Anthropology (Vol. 1, pp. 60-77): Institute for Social and Cultural Research, NICH.

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. London: SAGE Publications.

- Hyde, R. (2012). “Stoan Baas” people: An Ethno-historical study of the Gales Point Manatee community of Belize. Journal of Belizean Studies, 32(2).

- Iyo, A. (2000). Towards Understanding Belize’s Multi-cultural History and Identity. Belize: University of Belize.

Iyo, A., Froyla, T., & Humphreys, F. (2007). Belize New Vision: African and Maya Civilizations, heritage of a new nation. Belize: Image Factory Books. - Judd, K. (1990). Who will define US? Creolization in Belize. SPEAReport, 4, 29-40.

- King, E. (1999). Slavery in Belize: A family affair. Belize City, Belize: Tropical Books.

- Macpherson, A. (2003). Imagining the colonial nation: Race, gender, and middle-class politics in Belize, 1888-1898 Race and nation in modern Latin America (pp. 108-131). United States: The University of North Carolina Press.

Manzanares, M. Twenty Questions – The January Interview with Myrna Manzanares, President of the Kriol Council of Belize. Retrieved June 07, 2015, from http://www.belizemagazine.com/edition06/english/e06_05questions.htm - Manzanares, M. (2006). Traditional games of Belize. Belize: National Kriol Council and UNICEF.

NICH. (n.d. ). Local Social & Cultural Groups. Retrieved June 07, 2015, from http://www.nichbelize.org/iscr-institute-for-social-cultural-research/local-social-cultural-groups.html - Price, R. (1996). Maroon societies: Rebel slave communities in the Americas: JHU Press.

Shoman, A. (2010). Thirteen chapters of a history of Belize (2nd ed.). Belize City, Belize: Angelus Press Limited. - SIB. (2013). Belize Population and Housing Census 2010 Country Report. Belize: The Statistical Institute of Belize (SIB).

Wade, L., Herrera, Y., Woods, S., & Manzanares, M. (Eds.). (2005). Sohn stoari fahn Galyz Paint (Malanti) Paat 2 Some stories from the village of Gales Point (Manatee) Volume 2. Belize: The Belize Kriol Project. - Wilk, R. (2002). Television, time, and the national imaginary in Belize. Media worlds: anthropology on new terrain, 171-186.

How to Cite:

Manzaneres, M., & Cocom, R. (2015). Cultural change in Gales Point Manatee: Auto-ethnographic reflections from a community member. In N. Encalada, R. Cocom, P. Pelayo & G. Pinelo (Eds.), Research Reports in Belizean History and Anthropology (Vol. 3, pp. 47-54). Belize: ISCR, NICH. Retrieved from: [Insert BHA URL]

Download full article here!